Ilmiybaza.uz

ELEMENTS MAKING UP THE ENGLISH VOCABULARY. LATIN AND

GREEK BORROWINGS

Discussion Points:

1. Introductory notes

2. The foreign element in the English vocabulary

3. The Celtic element in the English vocabulary

Key Words: foreign element, word-stock, borrowing, native stock, loan-

words, ordinary English, commonly used, semantic groups.

Ilmiybaza.uz

ELEMENTS MAKING UP THE ENGLISH VOCABULARY. LATIN AND

GREEK BORROWINGS

Discussion Points:

1. Introductory notes

2. The foreign element in the English vocabulary

3. The Celtic element in the English vocabulary

Key Words: foreign element, word-stock, borrowing, native stock, loan-

words, ordinary English, commonly used, semantic groups.

Ilmiybaza.uz

The foundation and the framework of the English vocabulary is the native

element brought to Britain in the fifth century by the German tribes who eventually

overran the Britons.

Despite the borrowings already made before the Anglo-Saxons settled in

Britain and despite the large scale borrowings of the later periods native words are

still at the core of the language. They stand for the fundamental things dealing with

everyday objects and things.

The native stock includes auxiliary and modal verbs , most verbs of the

strong conjugations , pronouns, most numerals, prepositions and conjunctions.

The frequency value of these elements in the English vocabulary is not open to

doubt. Ordinary English and the vocabulary of colloquial speech embrace fewer

loanwords than, say, the language of technical literature. Almost all commonly

used English words are Anglo-Saxon in origin.

Many studies of English language seems to give undue prominence to the

foreign element, thus leaving an incorrect impression of the foundation of the

language.

The importance of the original word-stock is often overlooked largely because of a

multitude of foreign words incorporated in Modern English. Some foreign scholars

assumed that the development of English was mainly due to borrowing from

foreign sources.

It has been customary to subdivide the native element of the English vocabulary into

words of the Indo -European stock and those of common German origin. The words

having cognates in the vocabularies of different Indo- European languages belong

to the oldest layer. Familiar examples of such words are terms of kinship:

Father ( O.E.feeder); German- Vater, Greek- pater, Lat. Pater; Brother( O.E.

bropor); German- Bruder, Russian- брат, Lat.- frater; Mother ( O.E. modor);

German- Mutter, Russian- мать, Lat.- mater, Greek –

Daughter (O.E. dohtor); German - Tochter, Russian -дочь; Greek - thygater; Son

(O.E. sunu); German - Sohn, Russian - сын; Sanskrit - sunu from su.

Ilmiybaza.uz

The foundation and the framework of the English vocabulary is the native

element brought to Britain in the fifth century by the German tribes who eventually

overran the Britons.

Despite the borrowings already made before the Anglo-Saxons settled in

Britain and despite the large scale borrowings of the later periods native words are

still at the core of the language. They stand for the fundamental things dealing with

everyday objects and things.

The native stock includes auxiliary and modal verbs , most verbs of the

strong conjugations , pronouns, most numerals, prepositions and conjunctions.

The frequency value of these elements in the English vocabulary is not open to

doubt. Ordinary English and the vocabulary of colloquial speech embrace fewer

loanwords than, say, the language of technical literature. Almost all commonly

used English words are Anglo-Saxon in origin.

Many studies of English language seems to give undue prominence to the

foreign element, thus leaving an incorrect impression of the foundation of the

language.

The importance of the original word-stock is often overlooked largely because of a

multitude of foreign words incorporated in Modern English. Some foreign scholars

assumed that the development of English was mainly due to borrowing from

foreign sources.

It has been customary to subdivide the native element of the English vocabulary into

words of the Indo -European stock and those of common German origin. The words

having cognates in the vocabularies of different Indo- European languages belong

to the oldest layer. Familiar examples of such words are terms of kinship:

Father ( O.E.feeder); German- Vater, Greek- pater, Lat. Pater; Brother( O.E.

bropor); German- Bruder, Russian- брат, Lat.- frater; Mother ( O.E. modor);

German- Mutter, Russian- мать, Lat.- mater, Greek –

Daughter (O.E. dohtor); German - Tochter, Russian -дочь; Greek - thygater; Son

(O.E. sunu); German - Sohn, Russian - сын; Sanskrit - sunu from su.

Ilmiybaza.uz

Common Indo-European elements sometimes show considerable differentiation.

Such are some names for everyday objects and things, and natural phenomena:

fire (О. Е. fyr); German Feuer; Greek pyr.

moon (O.E. mono); German - Mond; Greek - mene;

night (О. Е. niht); German - Nacht; Russian - ночь; Latin - nox; Sanskrit -nakt;

tree (O. E. treo, treow); Russian -дерево ; Greek - drus-oak; Sanskrit dm forest.

water (O.E. woeter); German - Wasser; Russian - вода; Greek - hydoe; Latin-unda.

In the Indo-European stock we also find such English words as: bull, crew, cat, fish,

hare, hound, goose, mouse, wolf.

Here belong also quite a number of verbs: to bear, to come, to know, to lie, to mow,

to sit, to sow, to stand, to work, to tearl, etc.

Adjectives belonging to this part of the vocabulary may be illustrated by such as:

hard, light, quick, right, red, slow, raw, thin, white.

Most numerals in some Indo-European languages are also of the same origin. Words

of the common Germanic stock, i.e. words having their parallels in German,

Norwegian, Dutch, Icelandic. This part of the English vocabulary contains a greater

number of semantic groups.

The following list will illustrate their general character: ankle, breast, bridge,

brook, bone, calf, cheek, chicken, coal, hand, heaven, hope, life, meal, shirt,

ship, summer, winter and many more. Quite a number of adverbs and pronouns

also belong here.

It is of interest to note that words of the native stock are characterized by a wide

semantic range and grammatical valency. Their high frequency value and developed

polysemy are also well known. The native element is mostly monosyllabic.

It has been approximately estimated that more than 60% of the English

vocabulary are borrowings and about 40% are words native in origin. This is

due to specific conditions of the development of English.

The vocabulary of any language is particulary responsive to every change in the life

of the speaking community, to direct linguistic contacts, political, economic and

cultural relationships between nations.

Ilmiybaza.uz

Common Indo-European elements sometimes show considerable differentiation.

Such are some names for everyday objects and things, and natural phenomena:

fire (О. Е. fyr); German Feuer; Greek pyr.

moon (O.E. mono); German - Mond; Greek - mene;

night (О. Е. niht); German - Nacht; Russian - ночь; Latin - nox; Sanskrit -nakt;

tree (O. E. treo, treow); Russian -дерево ; Greek - drus-oak; Sanskrit dm forest.

water (O.E. woeter); German - Wasser; Russian - вода; Greek - hydoe; Latin-unda.

In the Indo-European stock we also find such English words as: bull, crew, cat, fish,

hare, hound, goose, mouse, wolf.

Here belong also quite a number of verbs: to bear, to come, to know, to lie, to mow,

to sit, to sow, to stand, to work, to tearl, etc.

Adjectives belonging to this part of the vocabulary may be illustrated by such as:

hard, light, quick, right, red, slow, raw, thin, white.

Most numerals in some Indo-European languages are also of the same origin. Words

of the common Germanic stock, i.e. words having their parallels in German,

Norwegian, Dutch, Icelandic. This part of the English vocabulary contains a greater

number of semantic groups.

The following list will illustrate their general character: ankle, breast, bridge,

brook, bone, calf, cheek, chicken, coal, hand, heaven, hope, life, meal, shirt,

ship, summer, winter and many more. Quite a number of adverbs and pronouns

also belong here.

It is of interest to note that words of the native stock are characterized by a wide

semantic range and grammatical valency. Their high frequency value and developed

polysemy are also well known. The native element is mostly monosyllabic.

It has been approximately estimated that more than 60% of the English

vocabulary are borrowings and about 40% are words native in origin. This is

due to specific conditions of the development of English.

The vocabulary of any language is particulary responsive to every change in the life

of the speaking community, to direct linguistic contacts, political, economic and

cultural relationships between nations.

Ilmiybaza.uz

2. The Foreign Element in the English Vocabulary

The English vocabulary falls into elements of different etymology. A study of loan-

words is not only of etymological interest. Words give us valuable information as to

the life of the nations concerned. The linguistic evidence drawn from such

observation is a very important supplement to our knowledge. Loan-

words have justly been called the milestones of philology.

The process of borrowing from other languages is due to the more or less direct

contact of one nation with another. This is to be regarded as a general linguistic

phenomenon.

No language is so composite as English; none so varied as to its vocabulary.

Strangely enough the Celts, who were the original inhabitants of England,

contributed little or nothing to this language save a few names of places. But in the

6th century, the invading Angles, Saxons and Jutes brought over the basic structure

of «English» speech, most common words, and for 500 years «English» was almost

wholly a Germanic language.

Then William the Conqueror sailed across the Channel and, by the Battle of Hastings

in 1066, Norman-French was superimposed on the West Germanic dialects. For

many generations these two languages ranged side by side, the one being spoken by

the Norman overlords, the other by the Saxon vassals and serfs.

As a matter of fact, three languages have contributed such extensive shares to the

English word-stock as to deserve particular attention. These are: Greek, Latin and

French. Together these languages account for so overwhelming a proportion of the

borrowed element in the English vocabulary that the rest of it seems much smaller

by comparison.

Loan-words have come, through travel, commerce, literature and in many other

waysj Accurate studies of certain parts of the loan element in English have not yet

been made. To discuss this subject with even an approach to com pleteness would

fill a whole volume.

By tracing the origin of loan-words and analysing the ways by which they

penetrated into the English language we can throw some light on the relations

Ilmiybaza.uz

2. The Foreign Element in the English Vocabulary

The English vocabulary falls into elements of different etymology. A study of loan-

words is not only of etymological interest. Words give us valuable information as to

the life of the nations concerned. The linguistic evidence drawn from such

observation is a very important supplement to our knowledge. Loan-

words have justly been called the milestones of philology.

The process of borrowing from other languages is due to the more or less direct

contact of one nation with another. This is to be regarded as a general linguistic

phenomenon.

No language is so composite as English; none so varied as to its vocabulary.

Strangely enough the Celts, who were the original inhabitants of England,

contributed little or nothing to this language save a few names of places. But in the

6th century, the invading Angles, Saxons and Jutes brought over the basic structure

of «English» speech, most common words, and for 500 years «English» was almost

wholly a Germanic language.

Then William the Conqueror sailed across the Channel and, by the Battle of Hastings

in 1066, Norman-French was superimposed on the West Germanic dialects. For

many generations these two languages ranged side by side, the one being spoken by

the Norman overlords, the other by the Saxon vassals and serfs.

As a matter of fact, three languages have contributed such extensive shares to the

English word-stock as to deserve particular attention. These are: Greek, Latin and

French. Together these languages account for so overwhelming a proportion of the

borrowed element in the English vocabulary that the rest of it seems much smaller

by comparison.

Loan-words have come, through travel, commerce, literature and in many other

waysj Accurate studies of certain parts of the loan element in English have not yet

been made. To discuss this subject with even an approach to com pleteness would

fill a whole volume.

By tracing the origin of loan-words and analysing the ways by which they

penetrated into the English language we can throw some light on the relations

Ilmiybaza.uz

between England and other countries. Even the barest enumeration of the successive

periods of borrowings will remind us of the history of the English people.

The influence of a foreign language may be exerted in two ways, through the

spoken word, by personal contact between the two peoples, or through the written

word, by indirect contact not between the peoples themselves but through their

literatures. The former way was more productive in the earlier stages, and the latter

has become increasingly important in more recent times.

It comes quite natural that words borrowed in a purely oral manner, as compared to

literary or bookish borrowings, have been quite successfully assimilated to the

English language and are often hardly recognizable as foreign in origin.

A consideration of the foreign element in language is not easy. A complete

discussion of the borrowed element in Modern English is hardly possible because of

the lack of accurate studies of the loan material, although some ideas of its character,

as well as of the time of its introduction, may be given with sufficient accuracy for

general purposes. In our study of the foreign element we shall leave out of account

entirely words occurring in Old and Middle English but lost to the

modern speech.

There are various degrees of «foreignness» (H. Marchand). Words may

appear as complete aliens borrowed from a foreign language without any change of

the foreign sound and spell ing. These words are immediately recognizable as

foreign words.

They retain their sound-form, graphic peculiarities and grammatical characteristics

and seem not to have broken their ties with the parent language completely.

Take such French borrowings as: ballet, bouquet, carte blanche, chauffeur, coquette,

coup d'etat, debris, finesse, phenomenon-phenomena, ragout, resume, regime, role,

trait, table d'hote, vis-a-vis, etc.

Certain foreign words are not felt to be aliens. They are completely or partially

assimilated with already existing native words and sometimes become

indistinguishable from the native element.

Ilmiybaza.uz

between England and other countries. Even the barest enumeration of the successive

periods of borrowings will remind us of the history of the English people.

The influence of a foreign language may be exerted in two ways, through the

spoken word, by personal contact between the two peoples, or through the written

word, by indirect contact not between the peoples themselves but through their

literatures. The former way was more productive in the earlier stages, and the latter

has become increasingly important in more recent times.

It comes quite natural that words borrowed in a purely oral manner, as compared to

literary or bookish borrowings, have been quite successfully assimilated to the

English language and are often hardly recognizable as foreign in origin.

A consideration of the foreign element in language is not easy. A complete

discussion of the borrowed element in Modern English is hardly possible because of

the lack of accurate studies of the loan material, although some ideas of its character,

as well as of the time of its introduction, may be given with sufficient accuracy for

general purposes. In our study of the foreign element we shall leave out of account

entirely words occurring in Old and Middle English but lost to the

modern speech.

There are various degrees of «foreignness» (H. Marchand). Words may

appear as complete aliens borrowed from a foreign language without any change of

the foreign sound and spell ing. These words are immediately recognizable as

foreign words.

They retain their sound-form, graphic peculiarities and grammatical characteristics

and seem not to have broken their ties with the parent language completely.

Take such French borrowings as: ballet, bouquet, carte blanche, chauffeur, coquette,

coup d'etat, debris, finesse, phenomenon-phenomena, ragout, resume, regime, role,

trait, table d'hote, vis-a-vis, etc.

Certain foreign words are not felt to be aliens. They are completely or partially

assimilated with already existing native words and sometimes become

indistinguishable from the native element.

Ilmiybaza.uz

Perfectly naturalized in usage they have been accommodated to the English

language by the substitution of English sounds for the unusual foreign ones. Such

are, for instance, many Scandinavian borrowings: call, die, husband, fellow, kill,

law, loose, low, meel, skirt, skin, sky, etc.

Naturalization of French borrowings is well known. A few examples will

suffice for illustration: river—(Fr. riviere) mountain — (Fr. montaigne, Lat. mons,

mentis) flower — (Fr. fleur) chain — (Fr. chaine)

A foreign word may be combined with a native affix, e. g. troublesome (trouble —

French by origin + the English suffix some); companionship (companion — French

by origin-j-+ the English suffix ship); faultless (fault — French by origin + the

English suffix less); uncertain (the English prefix un + certain — French by origin);

unconversable (the English prefix un •+• conversable — French by origin).

Relative borrowings or words that have somewhat changed their outer aspect and

got rather far in sense from what they used to be in their native sphere, e. g. travel

comes from the French travailter—to «toil».

The influence of one language upon another also makes itself felt in the so-called

translation-loans, e. g.:

English: by heart; local colouring; knight errant French: par Coeur; couleur; locale;

chevalier errant.

English: mother tongue; a slip of the tongue Latin: lingua maternal; lapsus linguae.

Most of the given words are international in character. Other examples are:

Procrustean bed — прокрустово ложе.

(After a legendary highwayman of Attica who tied his victims upon an iron bed

and stretched or cut off their legs to adapt them to its length. He was slain by The-

seus).

Sword of Damocles—Дамоклов меч.

(A flatterer whom Dionysius of Syracuse rebuked for his constant praises of the

happiness of kings by seating him at a royal banquet beneath a sword hung by a

single hair).

Sisyphean labour — Сизифова работа.

Ilmiybaza.uz

Perfectly naturalized in usage they have been accommodated to the English

language by the substitution of English sounds for the unusual foreign ones. Such

are, for instance, many Scandinavian borrowings: call, die, husband, fellow, kill,

law, loose, low, meel, skirt, skin, sky, etc.

Naturalization of French borrowings is well known. A few examples will

suffice for illustration: river—(Fr. riviere) mountain — (Fr. montaigne, Lat. mons,

mentis) flower — (Fr. fleur) chain — (Fr. chaine)

A foreign word may be combined with a native affix, e. g. troublesome (trouble —

French by origin + the English suffix some); companionship (companion — French

by origin-j-+ the English suffix ship); faultless (fault — French by origin + the

English suffix less); uncertain (the English prefix un + certain — French by origin);

unconversable (the English prefix un •+• conversable — French by origin).

Relative borrowings or words that have somewhat changed their outer aspect and

got rather far in sense from what they used to be in their native sphere, e. g. travel

comes from the French travailter—to «toil».

The influence of one language upon another also makes itself felt in the so-called

translation-loans, e. g.:

English: by heart; local colouring; knight errant French: par Coeur; couleur; locale;

chevalier errant.

English: mother tongue; a slip of the tongue Latin: lingua maternal; lapsus linguae.

Most of the given words are international in character. Other examples are:

Procrustean bed — прокрустово ложе.

(After a legendary highwayman of Attica who tied his victims upon an iron bed

and stretched or cut off their legs to adapt them to its length. He was slain by The-

seus).

Sword of Damocles—Дамоклов меч.

(A flatterer whom Dionysius of Syracuse rebuked for his constant praises of the

happiness of kings by seating him at a royal banquet beneath a sword hung by a

single hair).

Sisyphean labour — Сизифова работа.

Ilmiybaza.uz

(A crafty and avaricious king of Corinth condemned in Hades to roll up a hill a huge

stone, which constantly rolled back). Heel of Achilles — Ахиллесова пята.

(The hero of Homer's Iliad who became the Greek ideal of youthful strength, beauty

and valour. He was fatally wounded by Paris's arrow, which pierced his heel, where

alone he was vulnerable).

Translation-loans

are

not

less

characteristic

in

phraseology:

English

French

It goes without saying Cela va sans dire

with lost body a corps perdu

with sure stroke a coup sur

in mass, in a body en masse

at any cost coute que coute

better late than never mieux vaut tard que jamais

fall ill tomber malade

fine feathers make fine birds

make believe

not at all

reason for being

to a good cat, a good rat

la belle plume fait le bel oiseau

faire croire

pas du tout

raison d'etre

a bon chat, bon rat.

Latin

aut Caesar aut nihil

ad Kalendas Graecas

nulli secundus

quot homines, tot sententia

est modus in rebus

Ilmiybaza.uz

(A crafty and avaricious king of Corinth condemned in Hades to roll up a hill a huge

stone, which constantly rolled back). Heel of Achilles — Ахиллесова пята.

(The hero of Homer's Iliad who became the Greek ideal of youthful strength, beauty

and valour. He was fatally wounded by Paris's arrow, which pierced his heel, where

alone he was vulnerable).

Translation-loans

are

not

less

characteristic

in

phraseology:

English

French

It goes without saying Cela va sans dire

with lost body a corps perdu

with sure stroke a coup sur

in mass, in a body en masse

at any cost coute que coute

better late than never mieux vaut tard que jamais

fall ill tomber malade

fine feathers make fine birds

make believe

not at all

reason for being

to a good cat, a good rat

la belle plume fait le bel oiseau

faire croire

pas du tout

raison d'etre

a bon chat, bon rat.

Latin

aut Caesar aut nihil

ad Kalendas Graecas

nulli secundus

quot homines, tot sententia

est modus in rebus

![Ilmiybaza.uz

cum grano sal is

Engl ish

- either Caesar or nothing

- on the Greek Calends second to none

- so many men, so many minds -there is a medium in all things

- to take something with a grain of salt.

Phrases from foreign sources (barbarisms) are not often fully acclimatized. They are

almost always used as aliens printed in italics, or in inverted commas; such are many

French phrases, e. g.:

a propos - in connection with; bon mot - a witty saying;

de trop - too much or too many, superfluous; en regie - by rule;

entre nous - between ourselves; en route - on or along the way;

facon de parler - way of speaking; fin do siecle - end of the century; nature morte -

still-life; mon cher - my dear; vis-a-vis - face to face;

faux pas - a false step, a slip in behaviour;

laisser faire - non-interference;

mal-a-propos - ill-timed, out of place;

par exemple - for example;

savoir faire - the knowing how to act. Here are some examples of Latin and Greek

words and stockphrases which occur in Modern English with a good deal of

frequency. Most of them have won a permanent place for themselves not only in

English usage but in other languages as well.

English:

- presumptive, without examination

- for this case alone

- to infinity

- at pleasure

- in point of fact

- from the law

- from the chair, with high authority]

Ilmiybaza.uz

cum grano sal is

Engl ish

- either Caesar or nothing

- on the Greek Calends second to none

- so many men, so many minds -there is a medium in all things

- to take something with a grain of salt.

Phrases from foreign sources (barbarisms) are not often fully acclimatized. They are

almost always used as aliens printed in italics, or in inverted commas; such are many

French phrases, e. g.:

a propos - in connection with; bon mot - a witty saying;

de trop - too much or too many, superfluous; en regie - by rule;

entre nous - between ourselves; en route - on or along the way;

facon de parler - way of speaking; fin do siecle - end of the century; nature morte -

still-life; mon cher - my dear; vis-a-vis - face to face;

faux pas - a false step, a slip in behaviour;

laisser faire - non-interference;

mal-a-propos - ill-timed, out of place;

par exemple - for example;

savoir faire - the knowing how to act. Here are some examples of Latin and Greek

words and stockphrases which occur in Modern English with a good deal of

frequency. Most of them have won a permanent place for themselves not only in

English usage but in other languages as well.

English:

- presumptive, without examination

- for this case alone

- to infinity

- at pleasure

- in point of fact

- from the law

- from the chair, with high authority]](/media/image/elements-making-up-the-english-vocabulary-latin-and-greek-borrowings1400page_8.png) Ilmiybaza.uz

cum grano sal is

Engl ish

- either Caesar or nothing

- on the Greek Calends second to none

- so many men, so many minds -there is a medium in all things

- to take something with a grain of salt.

Phrases from foreign sources (barbarisms) are not often fully acclimatized. They are

almost always used as aliens printed in italics, or in inverted commas; such are many

French phrases, e. g.:

a propos - in connection with; bon mot - a witty saying;

de trop - too much or too many, superfluous; en regie - by rule;

entre nous - between ourselves; en route - on or along the way;

facon de parler - way of speaking; fin do siecle - end of the century; nature morte -

still-life; mon cher - my dear; vis-a-vis - face to face;

faux pas - a false step, a slip in behaviour;

laisser faire - non-interference;

mal-a-propos - ill-timed, out of place;

par exemple - for example;

savoir faire - the knowing how to act. Here are some examples of Latin and Greek

words and stockphrases which occur in Modern English with a good deal of

frequency. Most of them have won a permanent place for themselves not only in

English usage but in other languages as well.

English:

- presumptive, without examination

- for this case alone

- to infinity

- at pleasure

- in point of fact

- from the law

- from the chair, with high authority]

Ilmiybaza.uz

cum grano sal is

Engl ish

- either Caesar or nothing

- on the Greek Calends second to none

- so many men, so many minds -there is a medium in all things

- to take something with a grain of salt.

Phrases from foreign sources (barbarisms) are not often fully acclimatized. They are

almost always used as aliens printed in italics, or in inverted commas; such are many

French phrases, e. g.:

a propos - in connection with; bon mot - a witty saying;

de trop - too much or too many, superfluous; en regie - by rule;

entre nous - between ourselves; en route - on or along the way;

facon de parler - way of speaking; fin do siecle - end of the century; nature morte -

still-life; mon cher - my dear; vis-a-vis - face to face;

faux pas - a false step, a slip in behaviour;

laisser faire - non-interference;

mal-a-propos - ill-timed, out of place;

par exemple - for example;

savoir faire - the knowing how to act. Here are some examples of Latin and Greek

words and stockphrases which occur in Modern English with a good deal of

frequency. Most of them have won a permanent place for themselves not only in

English usage but in other languages as well.

English:

- presumptive, without examination

- for this case alone

- to infinity

- at pleasure

- in point of fact

- from the law

- from the chair, with high authority]

Ilmiybaza.uz

- in virtue of office

- hasten slowly

- in the matter of

- a rare bird, paragon

- of its own peculiar kind

- let everyone have his own

- an indispensable thing or condition

- an unknown country

- unwilling or willing

- from the beginning

- touch-me-not

- unsurpassed

- horrible to relate

Latin:

Apriori

ad hoc

ad infinitum

ad libitum

de facto

de jure ex cathedra

ex officio

festina lente

in re rara avis sui generic

suurn cuique sine qua non terra incognita volens nolens ab initio noli me tangere

nee plus ultra horribile dictu

Greek - eureka, i.e. I have found it (the exclamation attributed to Archimedes upon

discovering a method of determining the purity of gold and now expressing triumph

over a discovery).

Among the other points of interest presented by the foreign element in the English

language mention should be made of the so-called descriptive translation which can

Ilmiybaza.uz

- in virtue of office

- hasten slowly

- in the matter of

- a rare bird, paragon

- of its own peculiar kind

- let everyone have his own

- an indispensable thing or condition

- an unknown country

- unwilling or willing

- from the beginning

- touch-me-not

- unsurpassed

- horrible to relate

Latin:

Apriori

ad hoc

ad infinitum

ad libitum

de facto

de jure ex cathedra

ex officio

festina lente

in re rara avis sui generic

suurn cuique sine qua non terra incognita volens nolens ab initio noli me tangere

nee plus ultra horribile dictu

Greek - eureka, i.e. I have found it (the exclamation attributed to Archimedes upon

discovering a method of determining the purity of gold and now expressing triumph

over a discovery).

Among the other points of interest presented by the foreign element in the English

language mention should be made of the so-called descriptive translation which can

Ilmiybaza.uz

be exemplified by such combinations of words as: lay judge (заседатель), thick ring-

shaped roll (— boublik — бублик).

Semantic borrowings

The linguistic evidence drawn from the character of loan-words shows that due to

the influence of one language upon another words may undergo different semantic

changes. The English word dream, for instance, which originally meant

joy, music, has taken its modern signification from the Norse.

The word bloom (A. S. bloma — lump) which originally meant metal, a mass of

wrought iron from the forge or puddling furnace, has taken its modern sense

from the Norse blom, blomi—a blossom, flower of a seed plant;— chiefly

collectively, the flowering state; as, roses in bloom.

The modern verb dwell originally meant блуждать; its modern signification has

been taken from the Scandinavian dvelja — жить.

Semantic borrowings are comparatively more frequent in nouns. The noun gift in

Old English meant выкуп за супругу and then through implied association—

веселье, свадьба; under the influence of the Norse it has come to mean подарок.

The modern meanings of such words as bread (Old English— slice of bread), holm

(Old English — ocean, sea), plough (Old English — measure of the ground) have

also been taken from the Norse.

3. The Celtic Element in the English Vocabulary

During the Anglo-Saxon period the English language came into contact with three

other tongues which to some extent affected the vocabulary. These were, first, the

speech of the Native Celtic inhabitants; secondly, the Latin, and thirdly, the Norse.

Of these Latin was the only one which at that time added any appreciable number of

words to the language of literature.

The principal contact between English and Celtic speech was established by the

English settlement of the British Isles. Older books on English philology contain a

long list of words supposed to be derived from the Celts.

Ilmiybaza.uz

be exemplified by such combinations of words as: lay judge (заседатель), thick ring-

shaped roll (— boublik — бублик).

Semantic borrowings

The linguistic evidence drawn from the character of loan-words shows that due to

the influence of one language upon another words may undergo different semantic

changes. The English word dream, for instance, which originally meant

joy, music, has taken its modern signification from the Norse.

The word bloom (A. S. bloma — lump) which originally meant metal, a mass of

wrought iron from the forge or puddling furnace, has taken its modern sense

from the Norse blom, blomi—a blossom, flower of a seed plant;— chiefly

collectively, the flowering state; as, roses in bloom.

The modern verb dwell originally meant блуждать; its modern signification has

been taken from the Scandinavian dvelja — жить.

Semantic borrowings are comparatively more frequent in nouns. The noun gift in

Old English meant выкуп за супругу and then through implied association—

веселье, свадьба; under the influence of the Norse it has come to mean подарок.

The modern meanings of such words as bread (Old English— slice of bread), holm

(Old English — ocean, sea), plough (Old English — measure of the ground) have

also been taken from the Norse.

3. The Celtic Element in the English Vocabulary

During the Anglo-Saxon period the English language came into contact with three

other tongues which to some extent affected the vocabulary. These were, first, the

speech of the Native Celtic inhabitants; secondly, the Latin, and thirdly, the Norse.

Of these Latin was the only one which at that time added any appreciable number of

words to the language of literature.

The principal contact between English and Celtic speech was established by the

English settlement of the British Isles. Older books on English philology contain a

long list of words supposed to be derived from the Celts.

Ilmiybaza.uz

Modern investigation, however, has shown that the number of Celtic words in the

English vocabulary apart from numerous place names before the 12th century is not

very considerable.

Examples of Celtic loan-words appearing in Old English and preserved until the

present time are: down (hill), dun (colour), bin (a chest for corn). The words bard,

brogue, claymore, plaid, shamrock, whisky, for illustration, are all of Celtic

origin, but none of them existed in the English of the Anglo-Saxon period.

The influence of the Celtic upon English may be traced in names of places. This is

natural, since place names are commonly adopted in great numbers from the

aboriginal inhabitants of a country. Celtic names are common in all parts of England

though much more largely in the north and west and especially in Scotland and

Ireland.

Skeat registers 165 words borrowed directly or indirectly from the Celts, including

in this number words of uncertain origin supposed to be derived from the Celtic.

Here are a few words Celtic in origin which have acquired international currency:

budget, career, clan, flannel, mackintosh, plaid, and tunnel.

The Classical Element In The English Vocabulary

Latin 1. The Classical Element in the English Vocabulary

The value of knowledge of the classical element in the English vocabulary makes

itself quite evident.

It helps us not only to learn and remember the meaning of a very large number of

English words , but to discover shades of meaning that must always remain hidden

from anyone who is ignorant of Latin.

The Latin influence on English as on other Germanic languages begins so early and

is of such continuous nature that it merits separate treatment.

It is at first the influence of a living language, dating from old times; it persists as

the influence of a dead language down to the present day .

In modern times Latin has been adopted for scientific nomenclature. A Latin

nomenclature has the special advantage of being understood by scientists all over

the world, so the Latin has become a sort of common name-language for science.

Ilmiybaza.uz

Modern investigation, however, has shown that the number of Celtic words in the

English vocabulary apart from numerous place names before the 12th century is not

very considerable.

Examples of Celtic loan-words appearing in Old English and preserved until the

present time are: down (hill), dun (colour), bin (a chest for corn). The words bard,

brogue, claymore, plaid, shamrock, whisky, for illustration, are all of Celtic

origin, but none of them existed in the English of the Anglo-Saxon period.

The influence of the Celtic upon English may be traced in names of places. This is

natural, since place names are commonly adopted in great numbers from the

aboriginal inhabitants of a country. Celtic names are common in all parts of England

though much more largely in the north and west and especially in Scotland and

Ireland.

Skeat registers 165 words borrowed directly or indirectly from the Celts, including

in this number words of uncertain origin supposed to be derived from the Celtic.

Here are a few words Celtic in origin which have acquired international currency:

budget, career, clan, flannel, mackintosh, plaid, and tunnel.

The Classical Element In The English Vocabulary

Latin 1. The Classical Element in the English Vocabulary

The value of knowledge of the classical element in the English vocabulary makes

itself quite evident.

It helps us not only to learn and remember the meaning of a very large number of

English words , but to discover shades of meaning that must always remain hidden

from anyone who is ignorant of Latin.

The Latin influence on English as on other Germanic languages begins so early and

is of such continuous nature that it merits separate treatment.

It is at first the influence of a living language, dating from old times; it persists as

the influence of a dead language down to the present day .

In modern times Latin has been adopted for scientific nomenclature. A Latin

nomenclature has the special advantage of being understood by scientists all over

the world, so the Latin has become a sort of common name-language for science.

Ilmiybaza.uz

Few of such words have any place in the speech of common people, and those that

have gained a foothold have been adopted from the language of the learned. It is

impossible to estimate, far less enumerate, these later Latin words with absolute

accuracy.

Some idea of their character may be gained from the list in the appendix to Skeafs

Etymological Dictionary. Above all the New English Dictionary has been constantly

and unfailingly helpful.

Some idea of the Latin element may also be gained from the large number of words

in English with Latin prefixes and suffixes; yet some of the latter also appear in

Romance words.

. Early Latin loans The Germanic tribes, of which the Angles and Saxons formed

part, had been in contact with Roman civilization and had adopted several Latin

words denoting object belonging to that civilization long before the invasion of

Angles, Saxons and Jutes into Britain.

These words are typical of the early Roman commercial penetration . To this

No subsequent single influence on English has been equal in its effect to that of the

Norman Conquest which, as is known, began in 1066.

Loan-words adopted through the conquest of England by the Norman French and

the subsequent intercourse between the two nations extending through the whole

Middle English period are, no doubt, most important foreign adoptions in the

English vocabulary.

In books devoted to teaching English it has been customary to consider the French

element as but one division of Latin borrowings , which seems justified in the

strictest etymological sense. But which respect to English, French surely deserves a

separate treatment because of the great number of such adoptions arid the various

times at which they have entered.

The influence of Modern French on English has been by no means inconsiderable,

so that on this account it also deserves separate study from Latin and other Romanic

elements.

Ilmiybaza.uz

Few of such words have any place in the speech of common people, and those that

have gained a foothold have been adopted from the language of the learned. It is

impossible to estimate, far less enumerate, these later Latin words with absolute

accuracy.

Some idea of their character may be gained from the list in the appendix to Skeafs

Etymological Dictionary. Above all the New English Dictionary has been constantly

and unfailingly helpful.

Some idea of the Latin element may also be gained from the large number of words

in English with Latin prefixes and suffixes; yet some of the latter also appear in

Romance words.

. Early Latin loans The Germanic tribes, of which the Angles and Saxons formed

part, had been in contact with Roman civilization and had adopted several Latin

words denoting object belonging to that civilization long before the invasion of

Angles, Saxons and Jutes into Britain.

These words are typical of the early Roman commercial penetration . To this

No subsequent single influence on English has been equal in its effect to that of the

Norman Conquest which, as is known, began in 1066.

Loan-words adopted through the conquest of England by the Norman French and

the subsequent intercourse between the two nations extending through the whole

Middle English period are, no doubt, most important foreign adoptions in the

English vocabulary.

In books devoted to teaching English it has been customary to consider the French

element as but one division of Latin borrowings , which seems justified in the

strictest etymological sense. But which respect to English, French surely deserves a

separate treatment because of the great number of such adoptions arid the various

times at which they have entered.

The influence of Modern French on English has been by no means inconsiderable,

so that on this account it also deserves separate study from Latin and other Romanic

elements.

Ilmiybaza.uz

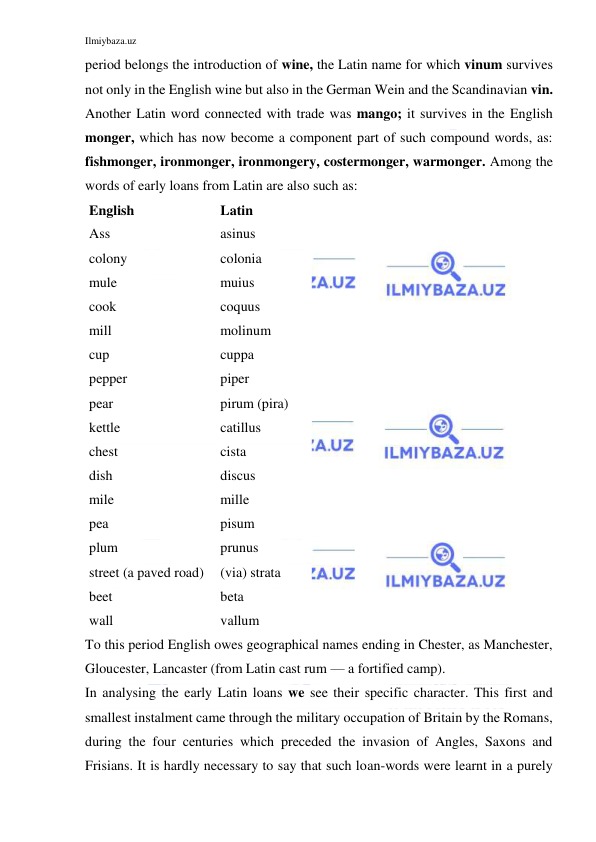

period belongs the introduction of wine, the Latin name for which vinum survives

not only in the English wine but also in the German Wein and the Scandinavian vin.

Another Latin word connected with trade was mango; it survives in the English

monger, which has now become a component part of such compound words, as:

fishmonger, ironmonger, ironmongery, costermonger, warmonger. Among the

words of early loans from Latin are also such as:

English

Latin

Ass

asinus

colony

colonia

mule

muius

cook

coquus

mill

molinum

cup

cuppa

pepper

piper

pear

pirum (pira)

kettle

catillus

chest

cista

dish

discus

mile

mille

pea

pisum

plum

prunus

street (a paved road)

(via) strata

beet

beta

wall

vallum

To this period English owes geographical names ending in Chester, as Manchester,

Gloucester, Lancaster (from Latin cast rum — a fortified camp).

In analysing the early Latin loans we see their specific character. This first and

smallest instalment came through the military occupation of Britain by the Romans,

during the four centuries which preceded the invasion of Angles, Saxons and

Frisians. It is hardly necessary to say that such loan-words were learnt in a purely

Ilmiybaza.uz

period belongs the introduction of wine, the Latin name for which vinum survives

not only in the English wine but also in the German Wein and the Scandinavian vin.

Another Latin word connected with trade was mango; it survives in the English

monger, which has now become a component part of such compound words, as:

fishmonger, ironmonger, ironmongery, costermonger, warmonger. Among the

words of early loans from Latin are also such as:

English

Latin

Ass

asinus

colony

colonia

mule

muius

cook

coquus

mill

molinum

cup

cuppa

pepper

piper

pear

pirum (pira)

kettle

catillus

chest

cista

dish

discus

mile

mille

pea

pisum

plum

prunus

street (a paved road)

(via) strata

beet

beta

wall

vallum

To this period English owes geographical names ending in Chester, as Manchester,

Gloucester, Lancaster (from Latin cast rum — a fortified camp).

In analysing the early Latin loans we see their specific character. This first and

smallest instalment came through the military occupation of Britain by the Romans,

during the four centuries which preceded the invasion of Angles, Saxons and

Frisians. It is hardly necessary to say that such loan-words were learnt in a purely